Before the current Director reported, the Coast Guard Investigative Service was not broken—but it was exhausted.

For years, CGIS agents and leadership operated in a constant state of reaction. We ran from fire to explosion, not because the mission demanded chaos, but because we were perpetually trying to prove our value to Coast Guard executive leadership that never fully understood who we were, what we did, or what authorities we carried. CGIS was expected to perform at the level of a mature federal investigative agency while being treated as an organizational afterthought.

What the organization needed was not disruption. It needed stabilization.

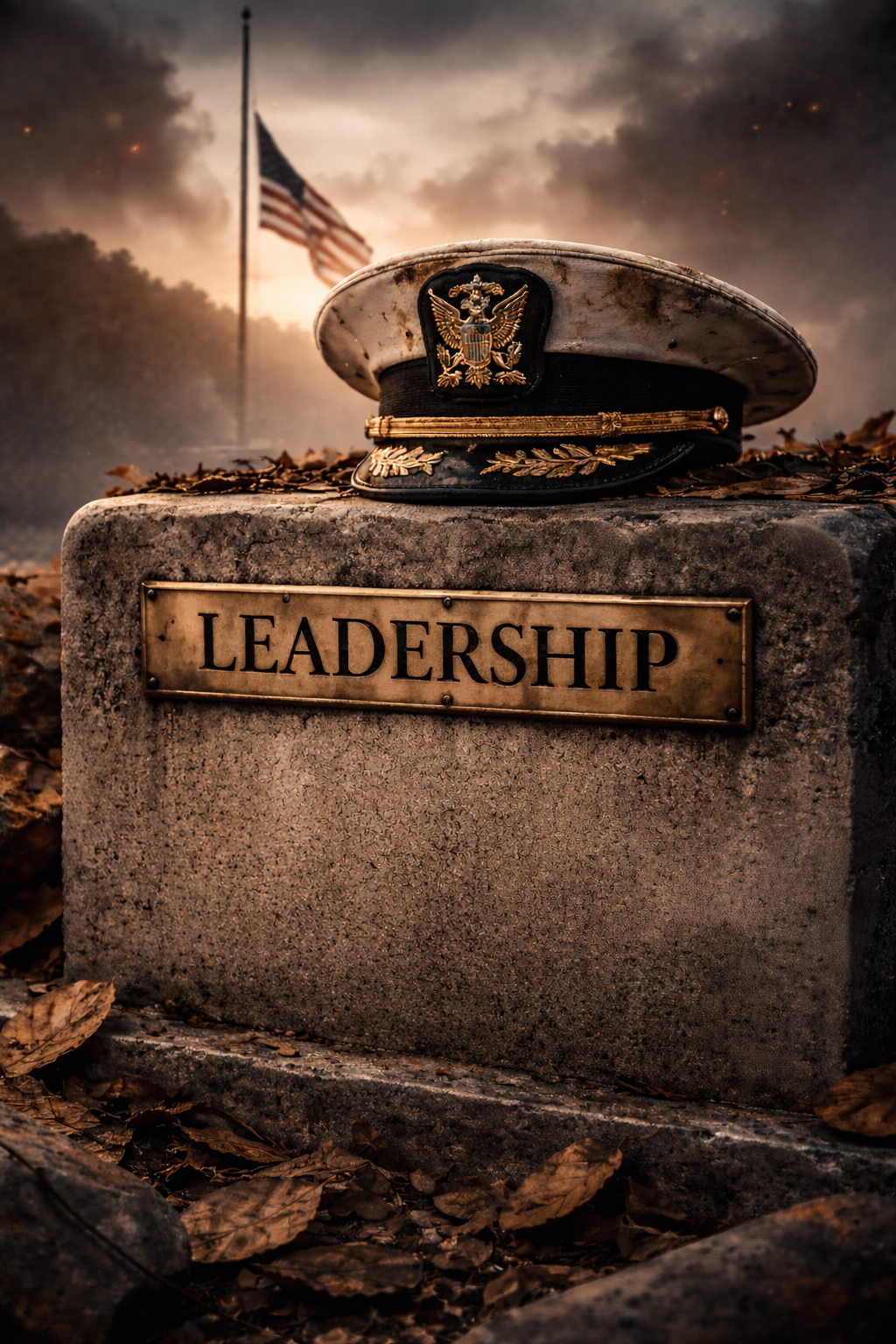

We needed a Director who would slow the tempo, calm the storm, and refocus CGIS on its core missions—protecting the Coast Guard, its people, and its integrity. We needed someone who would invest in agents, standardize operations, and ensure we had basic, non-negotiable requirements met:updated training, non-expired ballistic vests, appropriate investigative equipment, and consistent policies aligned with the broader Coast Guard enterprise. We needed leadership that understood CGIS could not function effectively without trust, predictability, and institutional backing.

Most critically, we needed a Director who understood that CGIS and the United States Coast Guard must operate synonymously—not as parallel organizations with a permanent cultural gap. That meant educating Coast Guard leadership on CGIS authorities and responsibilities, embedding our role into policy, and ensuring CGIS was automatically included in federal investigations touching Coast Guard equities. This could not be left to personalities or informal relationships. Coast Guard officers rotate. Enlisted members rotate. Agents rotate. Relationships dissolve. Without policy, CGIS is forgotten—again and again.

That is what the hiring panel continuously fails to understand.

The Coast Guard selected a Director without taking the time to understand CGIS as an organization. They assumed they already knew what CGIS needed, despite the fact that none of them had ever served within CGIS, led CGIS agents, or carried our investigative responsibilities. They did not understand our training pipelines, our jurisdictional boundaries, our relationships with U.S. Attorneys, or the delicate balance we maintain between independence and service to the Coast Guard.

From the moment the Director reported, it was clear that stabilization was not the goal.

He was immediately unapproachable. His demeanor, ego, and conduct conveyed a singular message: he had no interest in becoming part of the team. Almost instantly, CGIS Headquarters was turned against the field. An “us versus them” mentality took hold. Dissent was not tolerated. Questions were viewed as threats. Disagreement was punished. Within a short period, personnel at every level of CGIS Headquarters attempted to leave—retiring, transferring, or accepting pay downgrades simply to escape what was already being described as a hostile environment.

Senior leaders—career professionals with 25 to 30 years of service—were targeted for forced transfers. Some were given the minimum time possible to uproot their lives and move to Headquarters or retire. In several cases, these were leaders with barely a year left before mandatory retirement. That was not fast enough. The objective was removal, not transition.

Personal well-being meant nothing. Decades of service meant nothing. Careers built in service to the Coast Guard ended not with dignity, but with silence.

Multiple senior CGIS leaders were forced out with the full knowledge—and support—of Coast Guard leadership. Most received no awards. No recognition. Not even a thank-you for their service. They walked away heartbroken, not only by the Director’s conduct, but by the realization that the Coast Guard allowed it to happen.

In their place, the Director installed loyalists.

He created advisory positions for outside personnel—specifically former NCIS colleagues—whose primary value was not expertise, but allegiance. These advisors treated him not as a Director accountable to his workforce, but as a king surrounded by subjects. He could not be questioned. To do so invited professional destruction.

When these advisors departed after barely a year, they were publicly celebrated, awarded, and described as irreplaceable. Yet they left no lasting improvements, no strengthened relationships, and no operational gains. Their loyalty was to the Director, not the service. Again, the Coast Guard knew—and endorsed—the arrangement.

Field engagement offered no relief.

During his early visits to field offices, the pattern was unmistakable. Questions were deflected. Answers were political. Hard issues were ignored. Accountability was avoided. He viewed himself as a master of evasion—sidestepping responsibility rather than confronting reality. Listening was never the objective.

Instead, the Director pursued what he knew: NCIS.

After more than two decades at NCIS, he sought to remake CGIS in its image—not because it made sense, but because it was familiar. Naming conventions were changed because the existing structure was “too hard” for him to remember. Offices were renamed because they did not make sense to him. Organizational change was driven by personal comfort, not mission necessity.

Then came the investigations.

CGIS agents were directed to work cases well outside Coast Guard jurisdiction, with no prosecutorial path and no legal grounding. Coast Guard attorneys raised concerns. Field agents raised concerns. Sector commanders and district admirals raised concerns. None of it mattered. These cases aligned with the Director’s personal background and interests, not CGIS’s statutory mission.

Meanwhile, core CGIS responsibilities—drug interdiction support, migrant investigations, environmental crimes, and Coast Guard-specific corruption—were deprioritized. They did not interest him. What mattered were Director-driven “special interest” cases and DEI-branded initiatives that generated activity but rarely produced outcomes.

Resources were wasted. Time was squandered. Credibility suffered.

What emerged was not merely poor leadership, but gross mismanagement. Investigative priorities were redirected without authority, planning, or measurable benefit. Resources were expended on cases with no jurisdictional basis, no prosecutorial viability, and no Coast Guard nexus, while core mission requirements went unsupported. This was not an isolated misjudgment; it was a sustained pattern of waste and abuse of government time, funds, and personnel, driven by personal preference rather than operational necessity.

Compounding this failure was an extreme concentration of authority. The Director functioned as the sole decision-maker, refusing to trust even his remote interim Deputy Director, Assistant Directors, or Special Agents in Charge to exercise judgment within their roles. No meaningful decisions were permitted without his personal input. As a result, trust evaporated, ownership disappeared, and leaders were stripped of any sense of value or responsibility. The atmosphere at Headquarters became so toxic that input was neither welcomed nor believed. In multiple instances, personnel were pressured and intimidated to carry out actions they believed were improper or wrong—actions the Director himself avoided directing in writing or owning explicitly, thereby insulating himself from accountability while shifting risk downward.

At the same time, the Director fostered and sustained a hostile work environment. Fear replaced professional judgment. Dissent was punished. Questioning leadership decisions resulted in adverse consequences unrelated to performance. Agents and staff learned quickly that silence was safer than integrity. This environment was neither accidental nor temporary—it was enabled, reinforced, and normalized.

The damage extended beyond CGIS itself. The Director systematically eroded relationships with external law enforcement and prosecutorial partners by refusing to engage with counterparts who were not at his SES level. Routine coordination, case deconfliction, and relationship-building—foundational elements of federal law enforcement—were neglected or outright dismissed. Longstanding interagency trust deteriorated, not because partners were unwilling, but because engagement was conditioned on ego rather than mission. CGIS became harder to work with, less reliable, and increasingly isolated as a result.

When morale collapsed, the response was superficial. Gear was purchased—often equipment agents already had in excess, or items that were “nice to have” but not operationally necessary. The basics remained unaddressed. The gesture was performative, not strategic.

This was not leadership.

It was management driven by ego, insecurity, and personal preference—executed with the full knowledge and backing of Coast Guard senior leadership.

CGIS did not need a king.

It needed a steward.

What it received instead was executive control without leadership—and an organization fractured as a result.

The Result Was Catastrophic

Trust and confidence in CGIS leadership collapsed entirely as agents and Headquarters staff watched, in real time, the consequences of a Director who operated without moral grounding, integrity, or rational judgment. His conduct alienated the very workforce he was charged to lead. In the process, he unified agents and staff not behind him, but against him.

He became the failure point of the organization—the corrosive force leadership allowed to spread. And it spread because the Coast Guard endorsed it. Senior leadership knew his actions were causing irreversible harm to agents, to families, and to the institution itself. Yet no corrective action followed.

Words lost all meaning. Messaging lost all credibility. Everyone could see what was happening.

This was not merely about control or authority. It was about destruction. Careers were deliberately damaged. Professional relationships were severed. Seasoned adults—career agents and leaders—were pushed to emotional and professional breaking points. Not incidentally, but systematically.

The pattern revealed a singular preoccupation with self: image over people, legacy over stewardship, obedience over truth. Empathy was absent. Accountability was nonexistent.

The most damning failure, however, was not his alone.

The Coast Guard stood by as career agents, staff, and their families absorbed the fallout. It watched morale collapse and trust evaporate—yet chose silence. By doing so, it signaled that reputation mattered more than people, and optics more than integrity.

Most troubling is that none of this occurred in isolation or without visibility. The past two Commandants, current and prior Vice Commandants, two Deputy Commandant for Operations, senior enlisted leadership, Command Master Chiefs, and Reserve Command Master Chiefs were all aware. They were briefed. They reviewed multiple DEOCS survey results and correspondence from the field. They saw pages of agent and staff comments expressing fear of retaliation for questioning the Director, documenting plummeting morale, and describing a leadership climate that had become punitive and unsafe. Senior leadership knew forced transfers were occurring. They knew EEO complaints were being filed—and sustained—because of the Director’s repeated misconduct. They knew agents seeking mental health support were subsequently treated as liabilities rather than protected personnel. They knew suicidal ideations were increasing. They knew families were being impacted. They knew careers were being destroyed. They also knew this pattern constituted gross mismanagement, enabled a hostile work environment, resulted in waste and abuse of government resources, and inflicted lasting damage on CGIS’s credibility and relationships across the federal law enforcement community.

And yet, they chose not to intervene.

By their inaction, they validated the behavior, endorsed the harm, and allowed a leadership failure to metastasize into an institutional one. The consequences were foreseeable, observable in real time, repeatedly documented, and entirely preventable—had anyone with authority chosen accountability over silence.

That message was received—clearly and permanently.